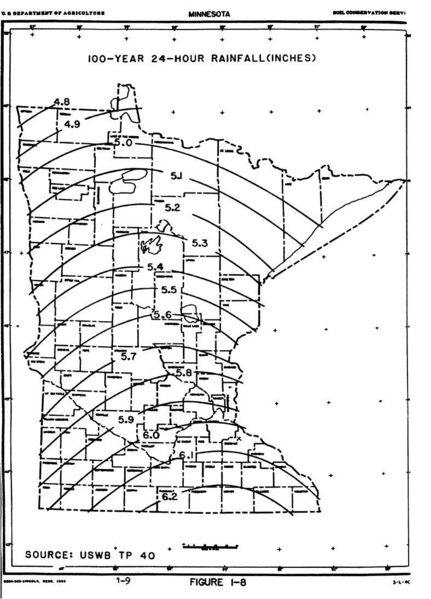

In 1961, the National Weather Service published a technical paper called “TP 40” that summarized rainfall data for communities in the eastern United States. Engineers who were designing roads and bridges could consult the tables in TP 40, get a sense for how much rain might fall every year in a given location, and calculate how large the stormwater pipes and culverts would need to be to prevent flooding during large storms.

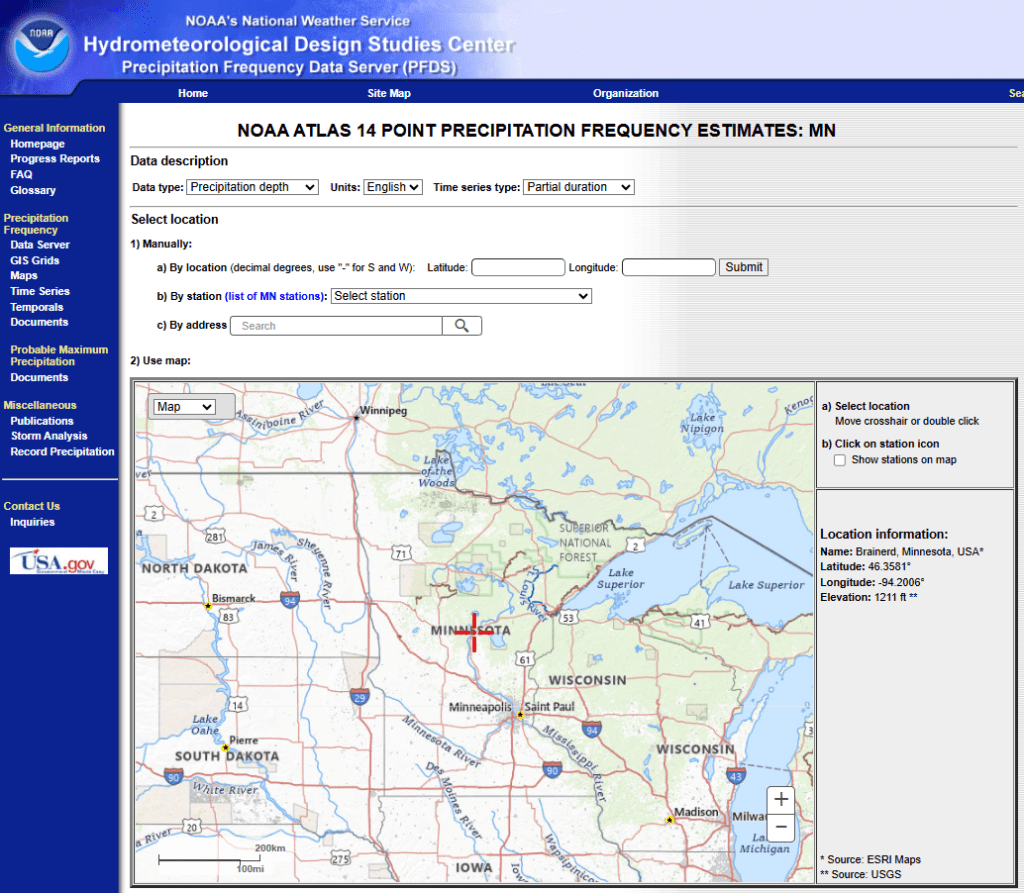

By the early 2000s, however, many people had begun to notice that Minnesota’s weather was getting wetter, with more rain per year and bigger storms happening more frequently. In 2013, the National Weather Service issued a new paper, called Atlas 14, which includes updated precipitation data and more details for design engineers. In the Twin Cities region, the “100-year” storm grew from being 6 inches of rain in a day to 7.5.

Now, watershed management organizations in the Twin Cities are taking the challenge one step further and are creating locally-specific models, designed to predict the impact of future rain and snow on streams, storm sewers, roads, bridges, lakes and homes in their communities.

One example is the Carnelian-Marine-St. Croix Watershed District, which is currently working with EOR Inc. to model the impact of 9.26 inches of rain in a 24-hour period of time, as well as 60-days of “unseasonably wet” weather, in Marine, Scandia, May Township, and Stillwater Township. The project is funded by a Local Climate Action Grant from the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency. A similar effort by the South Washington Watershed District led to the creation of a Climate Resiliency Plan in 2018, which identified vulnerable locations in Cottage Grove, Woodbury, Newport, St. Paul Park, and Oakdale.

One of the biggest challenges in flood resiliency planning is figuring out how to retrofit existing infrastructure to account for bigger storms once a community is already developed. In St. Paul, for example, the Ramsey-Washington Metro Watershed District recently completed a project to relieve flooding at Roosevelt Homes, a low-income public housing complex. Because the neighborhood is fully-developed and tightly packed with parking lots, roads, and rooftops, the watershed district had to take a multi-year approach, which included upgrading the drainage infrastructure, installing new native plantings in the neighborhood to capture and hold more water when it rains, and re-directing stormwater flows to avoid flood-prone locations.

In addition to upgrading stormwater infrastructure, watershed organizations are also looking for opportunities to store more water on the landscape in natural and restored wetlands. Two recent examples include the Brown’s Creek restoration in Stillwater and Trout Brook restoration in Afton, both of which re-created historic floodplains so that water is better able to spread-out and soak into the ground during snowmelt and heavy rain. Projects that restore historic wetlands on farm fields are also highly effective.